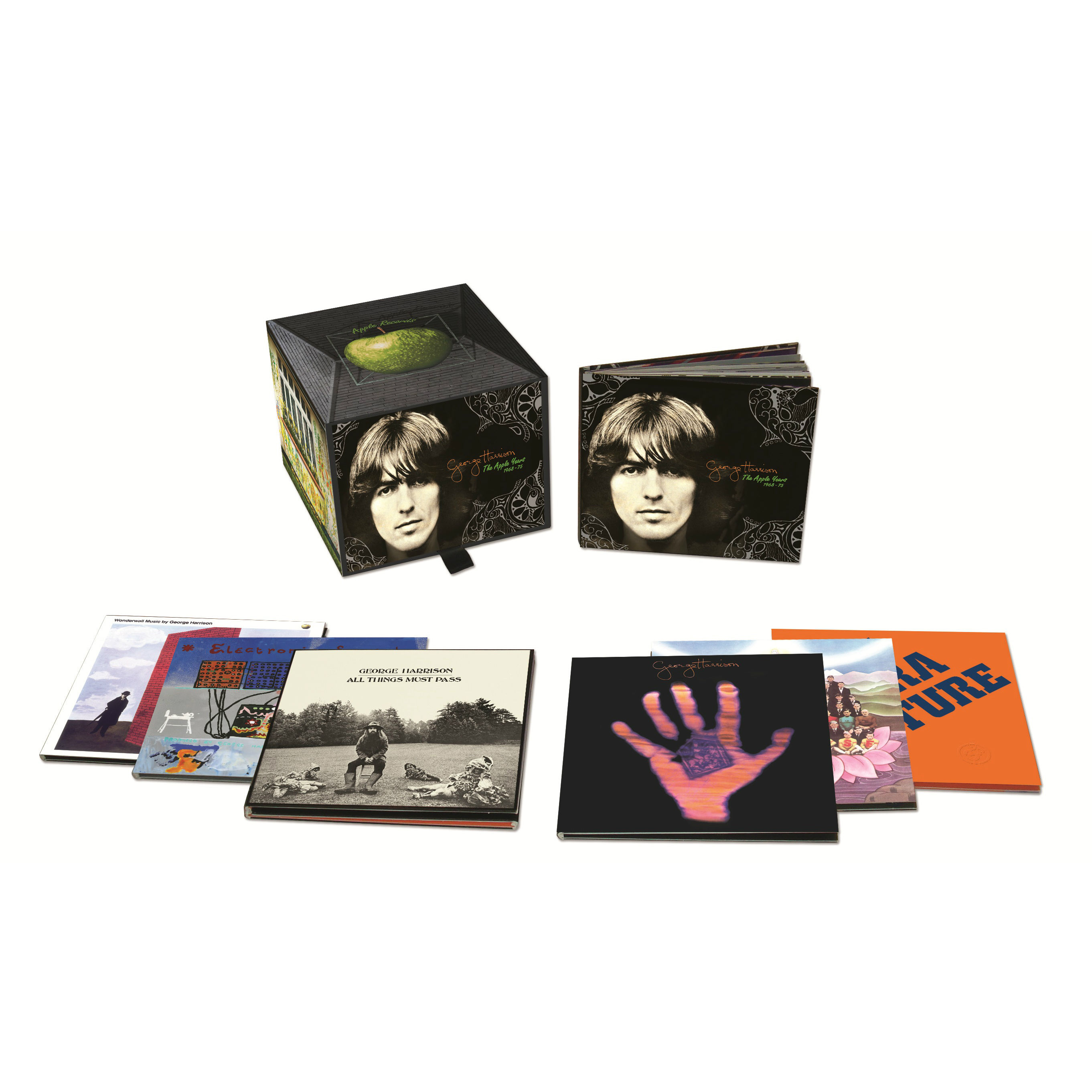

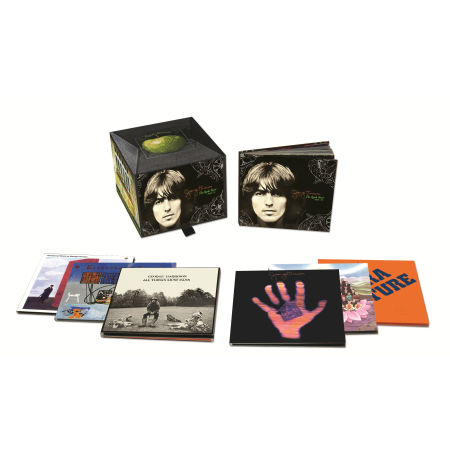

Between 1968 and 1975, George Harrison released six albums on the Beatles’ record label, Apple. The first record Harrison released was called Wonderwall Music, it was the soundtrack to a film directed by Joe Massot called Wonderwall. Maybe I should watch this film then.

Wonderwall tells the story of obsession. A scientist is obsessed with his work. His life revolves around it and he doesn’t notice anything around him. Not his coworkers, not his apartment. He lives amongst the stacks of papers that line the walls of his apartment.

Suddenly, in a rage, Professor Collins knocks a frame off his wall, exposing a hole. Through this hole he spies in neighbour. His boring life is exposed, and Professor Collins gets a glimpse into the swinging sixties.

Collins begins obsessing over Penny Lane, the woman next door, and the life lived by her and her boyfriend. Collins wishes he could be there living that life. Instead he’s stuck inside his own life. Living alone.

Wonderwall is more of a sketch than a film. There’s an unfinished quality to the story. There’s very little dialogue, Lane never speaks1, and we drift off into these fantasies of Collins’ mind. The fantasies are more reflective of the hippy genre than it is of the character’s senses. While he wishes to be a part of swinging London, he’s not on acid, leaving the audience wondering where these drug-fueled visions are coming from.

While Jane Birkin gets top billing as Penny Lane, she never speaks. Her role is to look beautiful and for Collins to leer. The brief moments of semblance of a characters are glossed over. We learn a brief moment of her life, slightly more than Collins knows. There’s an interesting question there: should the audience see more than Collins sees or should the audience see everything? I’d opt for everything make her a full character, but Massot goes for neither. The director instead shows us a quick glimpse into a possible world of Lane’s; never making her a full character, but making her more than Collins’ obsession. It’s a strange middle ground to be in, a horrible middle ground.

Consent is barely touched upon within the film. We see that Collins understands what he is doing is wrong, but continues to invade Lane’s privacy. Collins has a vision of his dead mother shaming him for his inappropriate actions, but never touches upon this again.

Consent is barely touched upon within the film. We see that Collins understands what he is doing is wrong, but continues to invade Lane’s privacy. Collins has a vision of his dead mother shaming him for his inappropriate actions, but never touches upon this again.

Making matters worse, Massot has Collins become the hero of the film. He saves Lane’s life seemingly justifying his actions.

This is where we truly see how poor of a filmmaker Massot is. None of the characters evolve or change, and the actions they take, the bad, horrible actions they take, never go unpunished, instead get rewarded. These actions are not rewarded for social commentary, but seemingly are rewarded due to lazy writing. Collins becomes a hero for breaking into Lane’s apartment, he ends up calling the police and cheating the woman out of the death she desires.

Collins doesn’t break into Lane’s apartment to save her. Instead he breaks in to be a creepy stalker. He just happens to come across her dying.

I don’t think the film will ruin my appreciation for the album Wonderwall Music. Well it’s not a well known album, it’s a great one. It’s nothing like any of George Harrison’s other works and shines because of it. Harrison experiments with Indian ragas and musical tropes he never had the ability to experiment with in The Beatles or as a pop musician.

Harrison’s work fitted the film quite wonderfully. While much of the film didn’t have any form of dialogue, Harrison’s soundtrack created a soundscape that helps transport the viewer away from the mundane as Collins’ wonderwall does for his boring life.

- I’ll get back to that shortly [↩]